Blind Boone Announces Retirement

On January 5, 1926, the internationally renowned pianist J.W. “Blind” Boone announced his retirement in an interview with the Columbia Missourian saying, “I am going to retire and live in the happiness I have wrought from others and in a final pursuit of those stray tones which I have not yet found in life.” Boone spoke publicly about retirement as early as 1921, but the Missourian interview was published after special New Years Eve performances on both KFRU, a radio station only a year old, and Stephens College Radio. Boone, who was rarely in his hometown for New Years, would keep a busy January schedule. His radio performances garnered an enthusiastic response from listeners, prompting an encore KFRU broadcast on January 13. On January 6, The Missourian advertised a concert in Columbia, proclaiming his now famous motto: “Merit, Not Sympathy Wins!” Yet Boone was not done touring, the next year, he played his last concert on May 31, 1927, in Virden, Illinois before returning to Columbia on doctor's orders. Boone never really retired and continued to plan performances while resting at his Columbia home. He died on October 4, 1927.

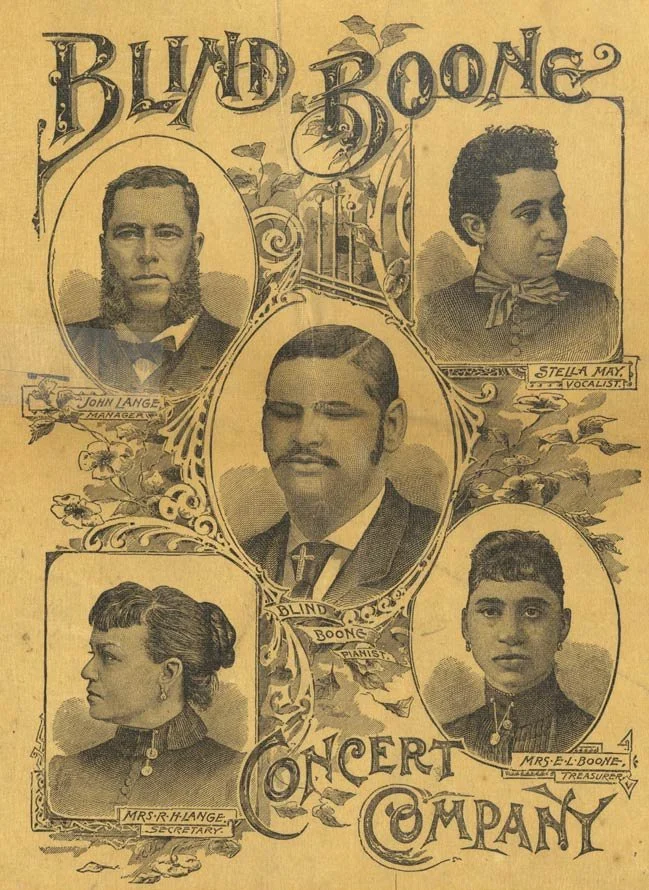

Blind Boone Concert Company advertisement

From Wikimedia Commons, original from the John William “Blind” and Wesley Boone Papers (C2883), State Historical Society of Missouri, Manuscript Collection

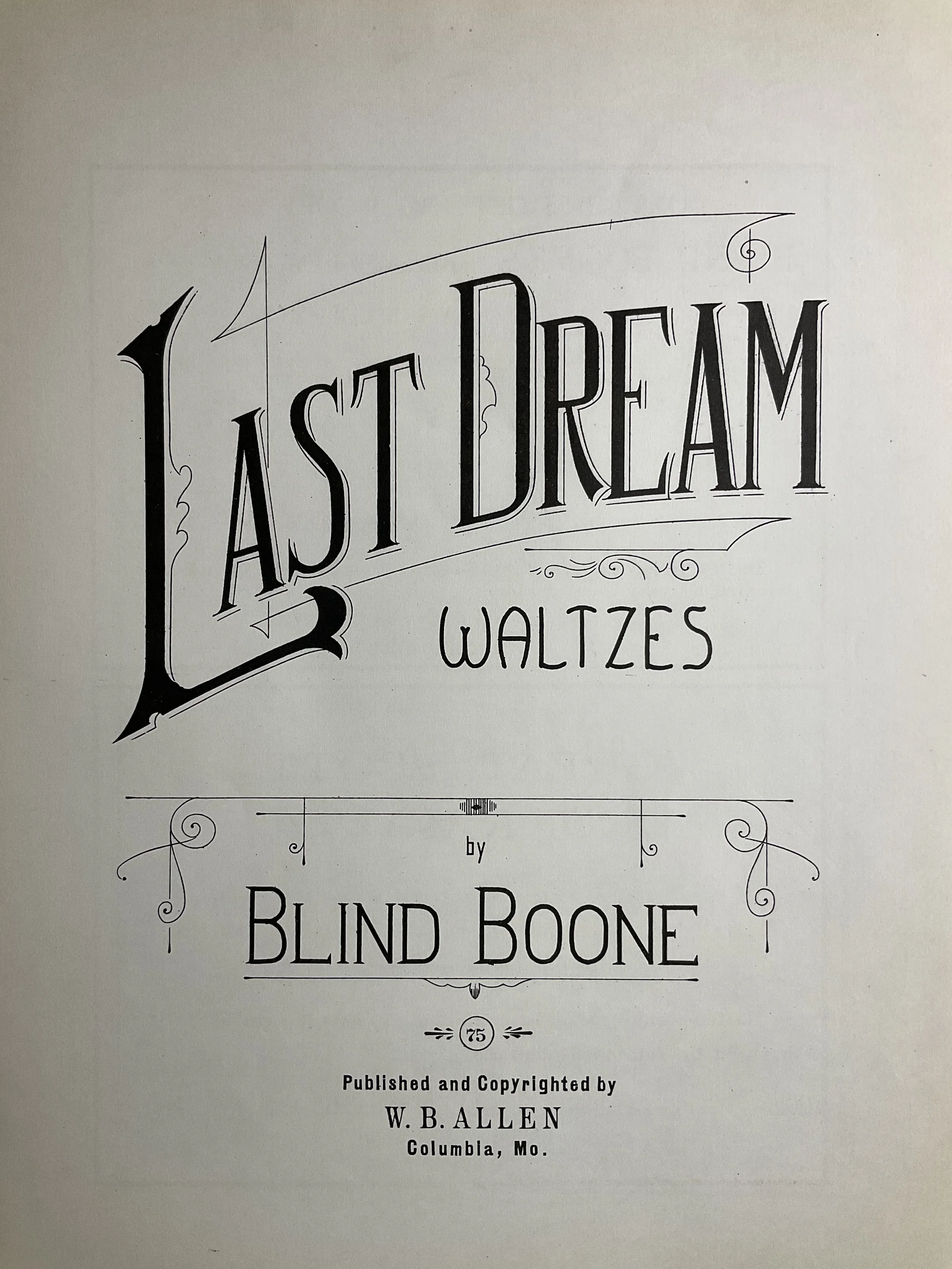

Coversheet of the “Last Dream Waltzs” by Blind Boone

From the private collection of Matthew Fetterly

Blind Boone saw himself as a pianist of the European classical tradition; his favorite composers were Liszt, Chopin, and Beethoven. However, it is difficult to overstate Blind Boone’s influence on ragtime, the musical form for which he is most remembered. Kjell Waltman, Swedish composer, performer, and music critic said:

“[Boone was] the first important African-American composer to create art music that is firmly grounded in the African-American musical idiom. In his imaginative caprices for piano in contemporary concert programs often referred to as "African Caprices" he utilizes, for example, pure ragtime rhythms, thus antedating by several years those compositions that are currently heralded as the first published ragtime compositions, and in his Rag Medleys, we find, as Peter Lundberg pointed out in 1975 in an entry for the foremost Swedish musical encyclopedia, Sohlmans Musiklexikon, the earliest documented example of boogie-woogie lines, as well as other astonishing examples of blues technique and these are but isolated instances in an amazingly inventive body of work! (It is, indeed, incomprehensible that while Scott Joplin and James Scott-both of whom Mr. Boone influenced and in the latter case, by all accounts, actively helped- have been honored with editions of their complete works-published by The New York Public Library and The Smithsonian Institution Press, respectively Mr. Boone himself has yet to be honored in this way.) Thus, on merit of his compositions alone, Mr. Boone, in my opinion, qualifies as a leading figure in American music of the late 19h (sic) and early 20 century.”

Performer and composer, Richard Egan, placed Boone among the greatest creative Missourians saying:

"Blind Boone is to music what Mark Twain is to literature and George Caleb Bingham is to painting a window that opens one's expanses into the life of Missouri when Missouri was the focal point of our nation's vibrant growth. ....[In our national development] there came a time when crude frontier folk art collided with European classicism and gave birth to a unique genre. Boone presented both the frontier and the classical realms, then capably assumed the role of bridge between two antithetical worlds and the new amalgamation. For this reason alone, any relic of his past is worthy of preservation."

The Blind Boone House after exterior restoration

From Wikimedia Commons by User:HornColumbia

The Blind Boone Home is one of Columbia’s greatest historic preservation success stories. Prominently located on Forth Street, next to Second Baptist Church, it was built around 1890 and given by John Lange Jr. as a wedding present to his sister, Eugenia, and her new husband, John “Blind” Boone. After Boone’s death, she continued to own the house until 1929. William and Parker Undertakers operated out of the home beginning in 1931. One of Parker’s former employees, Harold Warren, purchased the home and ran Warren Funeral Chapel for over 30 years. When Warren decided to sell the home and build a new building on Ash Street, a group of preservationists became involved. This group, known as the “Blind Boone House Project,” was formed after Mayor Darwin Hindman asked Debbie Sheals, a local architectural historian, to evaluate the structure’s potential. The project authored a report entitled “J.W. ‘Blind’ Boone: Restoration and Adaptive Reuse Options.” After a survey of public opinion and lengthy search for funds, the City of Columbia purchased the home from Warren in 2000. The challenging restoration process is described by the John William Boone Heritage Foundation on their website, as follows:

“When foundation board members entered the house, to their dismay, it was immediately apparent that significant termite damage had compromised the integrity of the studs and seal plates inside the exterior walls. Moreover, a long-neglected roof had allowed water to damage wall and roof structural elements. Soon after, the Boone Foundation was successful in securing funding from Missouri’s Historic Preservation Office for an architectural reuse plan. With the collaboration of the City of Columbia, they were able to secure funds to stabilize the house. In 2002, a group of community volunteers demolished the garage and the slow journey toward complete restoration began.

In 2006, the foundation submitted a grant application for $225,000 to Save America’s Treasures, a federal program that funds the restoration of historic public buildings. Although the application was not approved, the foundation continued to develop its capital campaign while preparing to reapply with a more competitive application to the federal program. Unfortunately, the economic crisis of 2008 resulted in the closing down of this program. Without funding for the restoration, the house once again began to deteriorate even as volunteers continued to work periodically on the interior demolition.

In 2013, the City of Columbia experienced a $1.4 million surplus. This proved to be the opportune moment for Mayor McDavid to endorse a recommendation for $500,000 to complete the restoration of the Boone home. Concerns about this amount resulted in a series of meetings to lower the budget so approval could be ensured. On June 3, 2013, the city council approved spending $326,855 to complete the restoration of the Blind Boone home. The foundation also transferred $16,500 to the city to supplement the budget for the landscaping. After demolition, the house was nothing more than a shell. Once the wood lathe was removed, the entire structure became unstable, so the entire house had to be reframed.”

The Blind Boone House before exterior restoration

From Wikimedia Commons by User:HornColumbia

The Blind Boone Home was first listed on the National Register of Historic Places on September 4, 1980, as part of “Social Institutions of Columbia’s Black Community.” Also listed were, Second Baptist Church, Douglas High School, Fifth Street Christian Church, and St. Paul A.M.E. Church. The home was individually listed on July 2, 2003 because of its association with Blind Boone. The nomination form describes it as follows:

“The John W. Boone House is a two-story frame house that was the home of internationally renowned ragtime pianist and composer, John William "Blind" Boone from the time of its construction around 1891 until Boone's death in August of 1927. . . [it] is located at 10 North Fourth Street in Columbia, Missouri. Set with its narrow facade facing Fourth Street on the west, this basically rectangular building occupies a lot measuring 71.25 feet by 122 feet. There is a small front yard sloping toward the street and a paved driveway south of the house that leads to the rear of the property. The original part of the house is two stories tall and measures roughly 46 feet by 45 feet. To the rear of the house is a 12-foot addition constructed early in the house's history. On the north side of the house there remains a single story addition measuring roughly 45 feet by 16 feet that was constructed in the 1948.

The front door of the house is located on the south elevation beneath a two-story porch. The porch is open at the ground level and was enclosed on the second story sometime prior to 1940. The original porch was also a two-story porch that was open with a balustrade encircling the second story. . . The house was originally sided with narrow weatherboard siding. A historical photograph taken in the 1890s reveals that pairs of exterior wooden shutters flanked the original windows. While the shutters have been replaced with modern metal ones, many of the original windows still remain. At some point in the 1930s or 1940's, the entire exterior of the house was covered with a layer of stucco. This was, in tern, covered with a layer of aluminum siding in 1970. These successive layers of exterior wall coverings have obscured all of the original window trim and have likewise obscured the historical integrity of the house as a whole.”

This CoMo 365 blog entry was constructed by Matt Fetterly using these sources:

Fuell-Cuther, Melissa; Blind Boone. (1915). Blind Boone : His Early Life and His Achievements Including "Early Life Stories"; Professional Life Incidents; Concert Reminiscences; Brief Life of His First and Only Manager; Also His Musical Compositions Arranged in Instrumental Selections of the Waltz Gallop Caprice Serenade Polka Together with His Reveries and Songs. Kansas City Missouri: Burton Publishing. OCLC 5024843.

Holland, Antiono (1980). Social Institutions of Columbia's Black Community (Partial Inventory). Jefferson City, Missouri: Lincoln University. Accessed at www.mostateparks.com on January 5, 2023.

Batterson, Jack A. (1998). Blind Boone, Missouri's Ragtime Pioneer. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. p. 69-74 ISBN 0826211984.

Salerno, Lucille; Olson, Greg (2003). National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Boone, John W., House. Columbia, Missouri: John William Boone Heritage Foundation. Accessed at www.mostateparks.com on January 4, 2023.

John William Boone Heritage Foundation. www.blindboonehome.org. Accessed on January 5, 2023.

Do you have ideas for future CoMo 365 topics? Did you notice an error?

Email me at como365@protonmail.com or leave a comment below.